Everyone is wrong about AI and Software Engineering

Reflecting on the discourse between OpenAI/Anthropic and Hacker News Commenters

There is a peculiar epistemological inversion happening right now where the least sophisticated observers of AI (like politicians) have stumbled into a more accurate model of reality than the most sophisticated ones. People who uncritically believed OpenAI’s marketing in 2023 and never updated their views are, by accident, closer to the truth about current capabilities than Hacker News commenters who pride themselves on rigorous technical thinking. This is not how it is supposed to work.

The HN consensus through most of 2024 and 2025 was that LLMs were useful for boilerplate and autocomplete but could not handle real software engineering: complex codebases, multi-file changes, genuine reasoning about system behaviour. Claude Sonnet 3.5 and GPT-4o were impressive demos that fell apart on brownfield production codebases. The skepticism was earned. If you tried to use these models for anything beyond simple scripts, you encountered hallucinated APIs, lost context, and confidently wrong solutions that took longer to debug than writing the code yourself.

The problem is that earned skepticism hardened into settled belief, and the belief has not been revisited despite fairly dramatic changes in the underlying reality.

November 2025 was an inflection point

The compressed release cycle of late 2025 represented a genuine step change that I think many people have not fully registered. Google shipped Gemini 3 Pro on November 18th and immediately topped the LMArena leaderboard, beating GPT-5 on Humanity’s Last Exam by nearly six percentage points. Anthropic released Claude Opus 4.5 six days later. OpenAI reportedly declared an internal “code red” and rushed GPT-5.2 out the door eleven days after Gemini 3, pulling the release forward from late December.

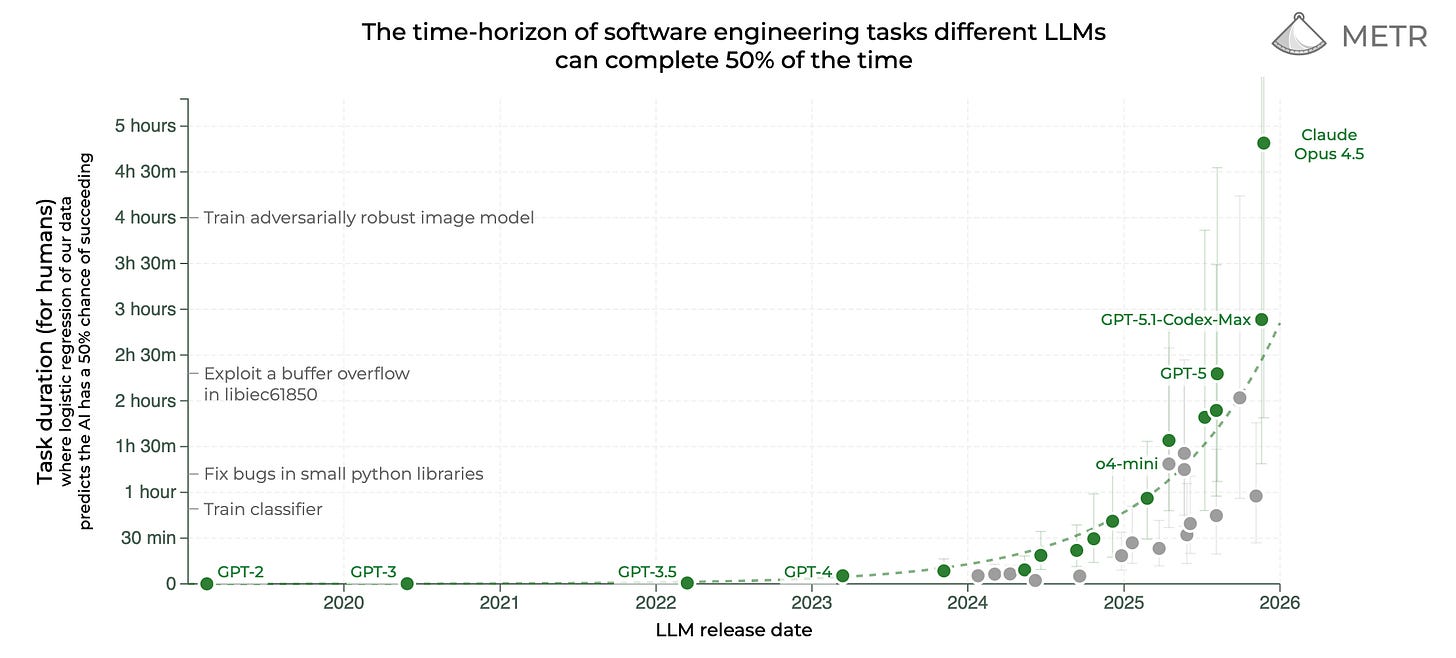

The benchmark numbers tell the story. Claude Opus 4.5 scores 80.9% on SWE-bench Verified (up from 33.4% scored by Claude Sonnet 3.5 v1), which tests the ability to resolve real GitHub issues in production repositories requiring navigation of large codebases and generation of patches that pass existing test suites. GPT-5.2 scores comparably. These are not greenfield toy problems; they are genuine bug fixes in real systems. METR estimates that Opus 4.5 can complete tasks that take human engineers nearly five hours. On Anthropic’s internal hiring exam for performance engineering candidates, a two-hour technical assessment, Opus 4.5 scored higher than any human candidate in the company’s history.

If your mental model of LLM capabilities is still calibrated to GPT-4o or Sonnet 3.5, you are working with year-old assumptions. Even the models from only twelve months ago genuinely cannot do what the models from two months ago can now do.

The epistemics of being right too early

Here is the uncomfortable part. The technically sophisticated crowd correctly identified that LLMs circa 2024 to early 2025 were overhyped for production software engineering. They formed a view, tested it against reality, found it accurate, and moved on. This is good epistemic practice. The failure mode is that changing your mind now feels like capitulating to the hype merchants you correctly dismissed before, so people find reasons not to do so. Every new benchmark gets explained away. Every capability demo gets nitpicked. The position becomes unfalsifiable.

Meanwhile, the people who naively believed the marketing never formed a sophisticated view to begin with. They just thought “AI will be able to code” because Sam Altman said so. They were wrong in 2023, wrong in 2024, and then the product caught up with the marketing and now they are accidentally right. They never had to update their beliefs because they were simply waiting for reality to match their beliefs.

This is how you end up with the strange situation where Hacker News threads are full of people arguing that LLMs “still can’t really code” while those same LLMs are being used to ship production features at companies that quietly stopped mentioning it because it is no longer interesting.

The marketing is also wrong, but differently

Before anyone accuses me of being an AI hypemonger, let me be clear: the claims coming from AI companies are also wrong, just in the opposite direction.

Dario Amodei has suggested AI will be writing most code within a year or two. Sam Altman’s messaging implies similar timelines for automating software engineering. The framing from all three major labs is that we are 6-12 months from AI replacing software engineers, and that companies should be preparing for this transition now.

This is wrong, but not for the reasons the skeptics think. It is not wrong because LLMs cannot generate code. They demonstrably can. It is wrong because it conflates code generation with software engineering, and these are not the same activity.

What software engineering actually is

Consider what happens when you build software professionally. You talk to stakeholders who do not know what they want and cannot articulate their requirements precisely. You decompose vague problem statements into testable specifications. You make tradeoffs between latency and consistency, between flexibility and simplicity, between building and buying. You model domains deeply enough to know which edge cases will actually occur and which are theoretical. You design verification strategies that cover the behaviour space. You maintain systems over years as requirements shift.

The part that involves typing code into a text editor was never the intellectually hard part. It was merely the slow and expensive part, requiring humans who had memorised syntax and APIs and could translate specifications into implementations accurately. This created a bottleneck that made the translation step feel important, but the bottleneck was never where the difficulty lived.

LLMs have removed the translation bottleneck, and in doing so revealed what was always underneath: specification and verification are the actual work. Knowing what to build, how to decompose it, and how to confirm it is correct. These problems are not solved by better code generation, they’re at best made slightly easier.

What actually changes

If this analysis is correct, the implications are significant but not what either the skeptics or the hype merchants predict. It is not “everyone keeps their job” nor “all SWE jobs disappear within a year.” It is that the skill profile inverts.

The value of knowing syntax, APIs, and framework conventions approaches zero. An LLM can look these up faster than you can remember them. The value of understanding distributed systems, consistency models, queuing theory, authentication architectures, and domain-specific requirements goes up, because these represent the physics of computation - the actual knowledge about how computation and systems behave. You cannot specify “make this eventually consistent” if you do not understand what eventual consistency means and when you would want it.

This suggests a strange inversion in education and hiring. The bootcamp-to-junior-developer pipeline optimised for the translation bottleneck: learn syntax quickly, memorise common patterns, churn through tickets. If the bottleneck moves to specification and verification, that pipeline produces the wrong skills. The traditional criticism of computer science education, that it is too theoretical and not practical enough, may flip entirely when the practical skills are automated and the theory is what remains.

Entry-level roles that were primarily translation (take ticket, write code, submit PR) may genuinely contract. Senior roles that are primarily specification and verification become more leveraged, because one person with good judgment and domain knowledge can now direct far more implementation than before. The concern that AI will hit entry-level jobs first might be correct, but for different reasons than people assume. Not because AI replaces juniors directly, but because the junior role was largely translation, and translation is what got automated.

The uncomfortable middle ground

The Hacker News skeptics need to revisit their assumptions. The models are genuinely capable now across a meaningful range of complexity, and dismissing every benchmark as “not real software engineering” is starting to look like motivated reasoning. The capabilities improved substantially in late 2025, and pretending otherwise because you do not want to agree with people who were premature in 2023 is not rigorous thinking.

The AI company executives also need a reality check. They are automating the translation layer, not the engineering layer, and the distinction matters enormously. Specification, decomposition, verification, domain modelling, and systems thinking are not fundamentally solved simply by generating code faster. Claiming that software engineering will be automated in 6-12 months reveals a fundamental confusion about what software engineering is.

English is becoming a programming language with a probabilistic compiler. You specify intent, the model generates code, you verify behaviour. The abstraction increasingly holds for the translation step. What remains hard is knowing what to specify, and that was always the actual job.